Samantha and Michaela Kendall

UPDATE

June 8, 2013

One of my readers, Merry, sent me the link to the article written by Hester Lacey about Samantha and Michaela Kendall entitled 'IN ANGER AS MUCH AS SORROW," which was published on November 16, 1997, in The Independent, excerpts of which I had posted in 2009 (see below).

I am now posting Ms. Lacey's full article, which is near the end of this post, because it is well worth the read...the terrible suffering and struggle parents and their children with eating disorders go through, with the outcome not always being positive.

ORIGINAL 2009 POST:

Over 10 years ago, I first heard of Samantha Kendall, who died from anorexia, as had her twin sister, Michaela, a few years earlier.

Samantha had spent time at the Montreux Clinic in Victoria, British Columbia, which was run by Peggy Claude-Pierre. Samantha left Montreux, and in December of 1999 the British Columbia government closed down the clinic citing that Peggy Claude-Pierre and her "clinic staff physically restrained patients, force fed, verbally threatened and mentally abused them." The closure of the clinic made headlines across Canada.

Losing one child to anorexia is heartbreaking, but losing two must be devastating. Suzy Kendall, the mother of twins, Michaela and Samantha Kendall, suffered this unbelievable heartbreak.

The following is an archived article which was originally published in The Independent (London)in 1997. Unfortunately, the author's name was not attached to the article, and the first portion of the article was missing from the archive.

"...lived in a succession of small rented flats in Birmingham. Then she [Suzy Kendall] missed a pill and by the time she went to the doctor, thinking she had a stomach bug, she was already four and a half months pregnant.

By this time she and her husband were already arguing; he would disappear for the day, while she worked selling petrol and valeting cars.

"When the doctor told me I was pregnant, I was inconsolable," she recalls. "We hadn't planned a child. He wasn't working, and I thought I couldn't keep working if I had a baby."

There were rows and reconciliations; Suzy got as far as filing for divorce at one stage. "My mother was furious and wanted to wash her hands of me. She said she would help to bring up the baby, I didn't need to be with him," she says.

Then her husband went to prison for nine months for burglary; it was her mother who was by her side when she gave birth to not one but two daughters: Samantha first, then 10 minutes later Michaela, on 12 May 1967. Everyone, including Suzy herself, was stunned by the surprise double-birth. Her own mother was not impressed.

"Mum didn't blame me as such - it was something beyond my control - but she did say, 'Why on earth did you have to have twins? How are we going to manage?'" Suzy recalls.

"On the third of June, my husband came out of prison. We tried to live together in Mum's house, but it didn't work out." More rows, more reconciliations. He thumped her; cash was tight. Two babies were hard work. "I was inexperienced, I'd never had anything to do with children - I was scared of them. I'd never even babysat before.

He left me for another woman when the twins were two and a half. I hadn't any money, I hadn't any prospects. I was hysterical. I thought my whole world had fallen apart, I couldn't bear it. I was still in love with him, I just didn't know what to do."

She gathered up the twins the morning he left and went round to her mother's house. "I was in bits, and she started clapping her hands and saying, 'Good, good! You're better off without him.' Then she came up with this idea. She said, 'You've got no money, you have got to go out to work.' She said she would give up her job and bring up the twins and I would pay her.

I moved in just round the corner from Mum and Dad so I could see them - there just wasn't room in the house for me to move in there permanently." Her mother, she says, was an authoritative figure. "Mum was a matriarch. What she said to do, you did. In retrospect, if I'd insisted and said I was going to bring them up myself, who knows what would have happened?"

So Suzy went out and found a job driving Transit vans. A number of children in the twins' class at school were being brought up by their grandparents, she says. "People assume the mother was up to no good when that happens, but there were a few kids in their class who were in the same position, due to different circumstances. I believed my mother knew best. When we had disputes about the twins, she would say, 'What do you know?' And I believed her - she'd brought up three daughters already, after all."

Suzy's mother, the twins' grandmother, had cooked for a living; she worked in the canteen at the GPO. "Mum was always cooking, so the twins did pile on the weight," recalls Suzy. "If the girls were ever sick or ill when they were young, she'd make sure they got a good meal inside them. They'd comfort-eat as well, back then.

I remember when my sister came from London and my mother met her off the train with the twins. And they always remembered this: my sister got off the train and said, 'Oh my god, Mum, they're enormous' - and they heard. They said to me they were so upset that on the way home they got a half-pound bar of chocolate each and ate the lot."

By the age of 14, Suzy estimates the twins weighed around 14 stone [196 pounds] each - she refers to them as "well-covered". At the time, she was working as a singer; despite their weight, the twins had the confidence to get up on stage with her in clubs and pubs round Birmingham, and both hoped for a musical career.

Neither shone academically. "They hated school because of all the taunts," says their mother. "They said they weren't accepted because they were fat. One boy called Michaela a fat blob and she hit him - they both got detention for that."

And then they decided to do something about their weight. Michaela and Samantha started dieting over the school summer holidays, the year they were 14. "Every time I went round there, they'd be sitting there with just an apple. My Mum said they were driving her mad."

Back in the early Eighties, awareness of anorexia was nowhere near as widespread as it is now - particularly not on a Birmingham council estate. Suzy had no idea what she was dealing with, as the twins each lost several stone over the summer break.

Samantha Kendall

Samantha Kendall

Michaela Kendall

At first she was concerned, but not unduly so. "Then I realised this was not just dieting, this was starvation. They'd go to the chemist and get a bar called 'Crunch and Slim' and they'd ration themselves to one of those a day. They'd have a bit of yoghurt, or an apple between them, or a bag of crisps, but only eat two crisps and throw the rest in the bin."

The twins' grandmother couldn't cope; Suzy tried to do what she could. "We'd sit and talk about it for hours and hours and hours. They'd say they realised they were being extreme, and promise they wouldn't do it any more. They promised and promised, tomorrow we'll have a proper meal. But they never did."

By the end of the summer, Suzy was sufficiently worried to take the girls to the family GP, who, she says, was baffled. "He just didn't know what to do." And so began a long round of doctors, professors, psychiatrists. At first, she believed that one of them would be able to help, but gradually her faith in the medical profession was eroded.

"I was brought up to believe these people were my superiors, and to treat them with respect. But nobody seemed to know what to do. There was one professor who thought he knew it all - he was about as useful as a chocolate teapot.

When Michaela was sectioned, he treated her for eight months in hospital. When she got the section lifted, she came home and died within two months. It was the same with Samantha. I went with her to his office. Sam said, 'Oh, but I'm eating now, professor,' and he said, 'Oh good, well that's all right then. Make sure you keep it up'. But she was lying between her teeth. She wasn't eating. I knew."

In their late teens, the twins were still managing to cling to some semblance of normality in their daily lives. After leaving school, they managed to get jobs and each started a steady relationship and lived with her boyfriend. But they were growing sicker, and both were in and out of hospital.

In the first interview published with the twins, in the Sunday Mirror in 1993, Michaela said they both became pregnant when they were 22. If they had continued with their pregnancies, perhaps their lives would have been different. But, said Michaela, "We looked in the mirror at the same time in our separate homes and thought, 'We're going to get fat.' So we decided to have abortions."

Samantha & Michaela

Samantha & Michaela

"They couldn't stick to any jobs," says Suzy. "They were Bluecoats and Redcoats in holiday camps, but they were told to leave because of the way they looked. In the end, the manager of the camp where they were working then, told them they were popular and everything, but the guests were appalled by having to sit with them over breakfast - they were putting people off their food. They were thrown out of cafes too."

In 1992, after a five-year relationship, Michaela's boyfriend gave her an ultimatum: the anorexia or the relationship. "I told him it had to be the anorexia," she said. She went back to her grandmother's house, and Samantha packed up, left her own boyfriend, and went to join her.

It was a fatal move. The two encouraged each other - before Michaela was eventually sectioned, Samantha was telling another tabloid interviewer that their daily diet was a couple of extra-strong mints at midday, a couple of crisps mid- afternoon, and an evening meal of a quarter of a slice of Slimcea bread and a sliver of black pudding.

Samantha was able to see how thin her sister was, even if she couldn't relate it to her own body. She said: "The competition makes it twice as bad. If Michaela says she doesn't want a cup of tea, then I won't have one, even if I'm desperate. When I say to her, 'Please, Michaela, eat a bit more, you look like a skeleton,' she snaps back at me, 'You're only jealous'."

Samantha holding Michaela. Michaela died in April of 1994

Samantha holding Michaela. Michaela died in April of 1994

After eight months in hospital, during which time she fought against forced-feeding, Michaela appealed against her sectioning and was allowed home; she died next to Samantha a few weeks later in the double bed they shared, weighing four and a half stone [63 pounds].

At this point, in desperation, with one daughter already dead, and the other dying, Suzy wrote to Chat, a women's magazine that pays readers for their true-life stories.

"I wrote to Chat, because no one was listening to me. Doctors were failing me, psychiatrists were failing me - the twins' own doctor didn't know how to handle it. It was a maze I couldn't get out of. I had to do something, there was nobody else. My mother was too old and she was ill herself - she's had two strokes. And that's how it all began."

She was taken aback but initially hopeful when the story was picked up internationally. "The Chat article opened up a whole storyline all over the world. But I didn't mean all this publicity to happen, I wouldn't have wanted it. What I was hoping for was someone who could come forward and cure Samantha. People are cruel, they say, 'She's doing this for publicity,' but that's nothing to do with it. The people out there haven't got a clue. It's no good judging me. I don't need judging."

Suzy Kendall might have made some wrong decisions, but if that is the case, she has paid for them many times over. Anorexia changes people both physically and mentally, and anorectics are not easy to get on with. As well as becoming thin and weak, chronic anorectics often grow a coat of downy hair on their skins; their teeth are ruined by vomiting. Constant, large doses of laxatives, self-administered to purge food from their bodies, can stop them controlling their bowels. Starving can also wreck the personality.

Samantha, says Suzy, used to be a joker, "a bit of a Lily Savage". She was also generous.

Samantha died in October of 1997

Samantha died in October of 1997

"If you admired something of hers, she'd give it to you - her earrings, her jacket. She was very giving and kind." But her condition changed her. "Anorectics become devious, like a junkie, not to be trusted. They are not the girls you knew. I went with Samantha to New York; we were on Maury Povich. Sam wanted to look round the shops, so we found ourselves in this store that sold paste jewellery. Sam loved jewellery, and we decided we'd buy little gifts for the people back home. So I'd got some things in my little wire basket and Sam had some in hers. Then all of a sudden, a great big diamante necklace dropped out of her sleeve." The owner of the shop came raging over as more jewellery fell out of Samantha's sleeves.

"I just didn't understand, because she had the money on her to pay for everything. The owner took us to the cash desk and made us pay for everything, or he'd call the police - half the stuff she didn't even want or like. To make matters worse, she was on big doses of laxatives. When we got out she was shaking like a leaf . . . she'd had an accident. She said, 'Oh Mum, I've bobbied myself' - that was the word we always used - 'I've got to go back to the hotel'. I was so angry with her, I said, 'You can go back by yourself, I've got to go and walk about and calm down.'"

After her appearance on American TV, Samantha went to the Montreux Counselling Clinic in Canada, in the summer of 1994. Her mother was hopeful; she still believes the Canadian method, which involves initial 24-hour one-to-one care and intensive counselling, is a model that should be adopted here.

Samantha put on weight, and gave a series of interviews in which she talked about her "cure". She even spoke of becoming a counsellor herself, and helping other anorectics. "Mum, you will be so proud of me when you see me," she wrote in a letter home. "I'm still determined to never starve myself again. It killed my darling Michaela, it's not killing me."

Then Suzy went over to visit her for two weeks. "I could see the problem was still there, and then out of the blue, she said, 'Mum, I'm coming home with you.' I said, 'No,' but she said, 'If you leave me here I'll die.' She was isolated, her twin was dead, she didn't know anyone. Everyone was thinking: 'She's had all that money spent on her, she should be getting well.' But there was one thing missing - her twin. Nobody could do anything about that."

Samantha came home, against Suzy's wishes, and announced in another interview that she was tired of being "wheeled out like a circus freak" to publicise the Canadian clinic's success. She admitted that she had continued to take laxatives while being treated.

"Because I was a high-profile patient, I knew that it would reflect on the clinic if I didn't appear to be responding," she said. "I knew I was good for attracting other fee-paying patients. Everybody wants to be able to say, 'I got Samantha Kendall better'."

Sadly, she was far from better. "But she was 27 years old and I couldn't dictate to her," says Suzy. "She insisted that she needed to come home. She said, 'I can't wait to see the Yew Tree shopping centre' - it's our local shopping centre. I said, 'You're surrounded by mountains and blue sea and you want to see the bloody Yew Tree!' But she came home, and she lived here with me and Bob for 12 months. I tried to persuade her to go back, but once a Taurean's mind is made up, they don't budge."

Bob's sales job took him out on the road a lot, and when he was away Samantha slept in her mother's bed. "She insisted on sleeping with me, she said she felt safe. But I knew she was back on laxatives because of the sheet the next morning - Bob used to go mad."

Suzy's second husband Bob, a patient and kindly man who has been, she says, more of a father to the girls than their natural one, was by now reaching the end of his tether. Their son, born when the twins were just starting their illness, also suffered, becoming hyperactive and difficult as a child. He has since left home.

Samantha went back into hospital towards the end of 1995, a year after leaving Canada. "She was there for four months, in a medical ward - one for physically ill people, no place for someone with her condition," says her mother bitterly. "I went on and on about it to them, but they said, 'Oh, we have to get the body right first.' They were doing everything arse-about-face, I knew that it's the mind you have to sort out. They said I didn't know enough to give them orders. I wasn't giving orders, but I knew they were wrong."

Samantha had other problems as well. "She was allowed out of the building and out of the grounds - she just went back there to sleep," says Suzy. "And by now she was drinking too. They called me at 4 am one morning and said get over here, Sam's dying. When I went over I knew she'd been drinking - she was going out and buying it. The hospital's attitude was just, 'Leave Samantha alone, she'll get better.'

I went to see her every single day. Our marriage was in jeopardy - I spent more time with her than with Bob." This, she says, was one reason that Samantha elected to move back not to the family home but into a nearby council flat, alone. "She made me promise I'd say she was homeless," says Suzy in a small voice. Up to now, she has kept her composure; anger has carried her through, but now she is close to tears.

"She said she wanted her own independence, a flat of her own. She said, 'I know what I'm doing to you and Bob. If I come back and live with you it will all start all over again.' I told her to come back to us, but she said she wouldn't live far away, so I agreed. The council offered her a wonderful flat."

Suzy helped Samantha decorate, painting a seascape and fluffy pink clouds on the walls. Samantha then started to refuse all help. Suzy visited every day and tried to persuade her to come back home. "Some days she wanted to live. But other days she'd say, 'I don't want to be here. Why don't you all leave me to die. If you leave me here I'll be able to drift away into oblivion.'"

The medical health officer assigned to her case tried to persuade her to at least go and stay with her mother for a while, where she would be looked after, but she refused. It became clear that her condition was worsening dramatically, and eventually, this summer at the beginning of July, she was sectioned by her medical health worker, and put first into a medical ward.

When Suzy next saw her daughter, she was semi-conscious. "She had two drips in each arm and a feeding tube in her nose, and she was slurring her speech as if she was drunk. She went into convulsions, her eyes were rolling back in their sockets . . . "

Samantha was then moved to a psychiatric unit. "It's a posh name for a nut house. They sent her there against my wishes and they didn't even tell me they had moved her - when I rang the first hospital she'd been in, they said, 'Sam's not here any more,' and I thought she'd died. When I went to see her, she was in tears, she was out of it, she was clinging to me. She thought they were going to kill her, and that they were making blue films about her. She said I was an actress, and Bob was an actor, and we were all out to destroy her. She was in with schizophrenics, drug addicts, raving alcoholics throwing the furniture about. She was terrified. One night there was fighting and screaming, the police were called and all the staff were running around with blood on their clothes - she didn't know why."

Suzy and Bob consulted a solicitor, to try and obtain Samantha's release, and the sectioning was lifted on 25 September. Samantha died on 20 October . "When she came out she was completely mental," says Suzy. "I couldn't have the radio or TV on, because she said they were planning her death. I had tried to cope with the anorexia, but I couldn't stand the mental disorder. I couldn't cope with it. It was the same with Michaela - all the same mistakes."

And she weeps. Samantha went into her final coma at Suzy's house, where she spent the last week of her life. She said that Michaela had appeared to her and she was ready to die. Suzy says they later discovered bottles and wrappings that suggested she had taken an overdose of paracetamol, to which she was allergic.

The night before she died, Samantha ate half a kebab and gave the other half to Rupert, Suzy and Bob's Akita puppy. Rupert and Samantha were both violently sick in the night but Suzy put it down to food poisoning rather than anything more serious.

"I felt terrible. The paramedic told me off - he said, 'Why the bloody hell have you left it this long to call, she's in a coma.' I didn't realise. She was always so lethargic and tired. They put her on a life-support machine but I think she was already gone."

Suzy Kendall believes that, with hindsight, Samantha was doomed when Michaela died. "She had to suffer for three years and six months before she joined her. She missed her twin so much she didn't want to live without her. Twins have a real uncanny bond, and it's so strong. They aren't like ordinary siblings. You can call me a loony, but Michaela came for Samantha. They are together now. No one ever split them up."

Her life, and the lives of her husband and son, have been poisoned by anorexia for the past 15 years. And although she denies any guilt, she does say, sadly, "I can't do anything right. I'm a real Calamity Jane."

What will she do now? She intends to campaign for further recognition of anorexia. But it's difficult to see exactly what she would like to achieve. "The government should do something," she says vehemently. But what? And she is tired. This is the end of a long effort. "I deserve some sort of solace and peace now. I won't get away unscathed from this, I won't make old bones. But I don't care any more. There is nothing as bad as this that can happen."

Suzy Kendall's role in her daughters' lives and deaths is one that fascinates people. "Why didn't their mother make them eat?" is a question that comes up over and over again. "Why didn't she make the doctors do something?" But making someone eat is not easy. At one point, Suzy was physically holding Samantha's jaws together to try to stop her bringing up the food that would have saved her; how was she to make her daughter eat - physically hold her down and force food down her throat?

I am the same age to within a few weeks as the Kendall twins would have been, had they lived. Among my close friends are two recovered bulimics, one recovered anorexic (she now sweats it out at the gym every week) and half a dozen others who have been on a diet of one kind or another since their teens. I am very glad that none of us ever strayed so far down that slippery road that we could not or would not come back; because, whatever one may think of Suzy Kendall and the others responsible for the twins' care, if a young woman decides categorically that she is going to starve, there seems to be very little that anyone can do."

Samantha and Michaela, rest in peace.

"IN ANGER AS MUCH AS SORROW

The Morning of Suzy Kendall's daughter's funeral, there were reporters camped on her doorstep. Funerals normally command the utmost respect; but even on such a day, the phone didn't stop ringing. As she was leaving to go to the service, it shrilled out again; it was a television channel requesting an immediate interview.

Suzy's daughter was Samantha Kendall, the "celebrity anorexic" who died last month, aged 30, weighing less than five stone. The tabloids saluted their mascot anorectic: "brave Sam died peacefully" announced the Mirror. In fact the last few months of her life were anything but peaceful, and bravery had long since gone out of the window, along with dignity and sanity.

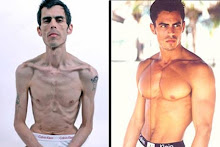

Samantha's ashes are now buried next to those of her twin sister Michaela, who succumbed to anorexia three years ago. The "anorexic twins" achieved international notoriety in May 1994, when Samantha appeared in newspapers and on television, looking like a concentration-camp inmate, little more than a skeleton covered in skin, her face striped with a mask of garish make-up meant to make her emaciated cheeks look even thinner.

Her twin sister had just died; Samantha herself did not have long to live, without urgent help. Her horrific appearance provoked worldwide shock and sympathy; an appeal for funds raised pounds 66,000 to send her to Canada to be treated at a pioneering anorexia clinic. And for a while she seemed to recover. She put on weight, and claimed to be "cured". But Samantha abandoned her treatment and came home to Birmingham before her course was completed; it then took her three years to starve herself slowly to death.

NOW THE reporters have abandoned Suzy Kendall's front lawn, and inside the house, too, it is probably more peaceful than it has been for years - only the radio is murmuring in the background. The house is one of a long row on a curving tree-lined street with deep grass verges, that snakes through a neat and well-kept Birmingham council estate. It's a quiet place, but the neighbours have become used to ambulances sweeping up at all hours of the day and night to the Kendall house. Suzy has spent the last few years on an endless round of ferrying her daughters back and forth from hospital, visiting them, chasing doctors and social workers and psychiatrists, answering hysterical early-hours calls for help, calling paramedics and washing linen and mopping up - an anorexic death is a messy, prolonged and ugly one.

Now all that is over, and Suzy Kendall is taking stock of the last three decades. It has been a hard time and a confusing one for her, and now for the first time she is able to look back and see it as a whole. Over the course of an afternoon, her story pours out. She is very aware that, in the eyes of the world, she is considered to be at fault for the deaths of her daughters. To have one anorexic daughter, it has been implied, is bad luck; have two, and there is something more sinister afoot. Initial sympathy for her in the press gave way to criticism, and she has been accused of manipulating the twins and enjoying the media limelight.

And that makes her both angry and defensive. If, she says, you have not experienced the horror of watching your children starve, it is hard to imagine just what it is like. Her voice rises almost to a shout. "When I've read things before about me not caring and saying I'm after notoriety - it's not true. It's been dreadful. I've lost my two daughters, I've lost them both, they're gone forever. I hope those out there, when they read this, I hope they don't judge anyone who tries to save their own children. If this happened to their children, what would they do? What would they do, tell me that? People ask me, 'What did you do for them?' People ask if I feel guilty that I didn't do enough. If I'd done any more I'd be dead myself."

Suzy appeared on television and radio here and in the US to publicise the twins' plight; forthright and salty, she made a good interviewee. On the day of Michaela's death, 20 April 1994, she was on the Maury Povich Show, an American chat-show, appealing for help. Samantha herself, in an interview two years before she died, was quoted as saying, "Mum likes the glory, that's what people have been saying. Sometimes I wonder whether she wants me here not out of love but to do a few shows and go to New York."

But for every hour spent under the lights of a glamorous television studio, there have been many nights like the one on which Samantha rang, begging for help - Michaela had slit her wrists and locked herself in the bathroom. Suzy hurried round to her own mother's house, where the twins were living, and threatened to break down the bathroom door; Michaela emerged, dripping blood, pushed her way out and ran shrieking into the night, leaving behind a bathtub "half-full of vomit".

SUZY IS now 50. She is small and blonde, with a deep Birmingham accent and a streetwise air. She looks battered by life; there are deep circles under her eyes, and her nails are bitten to the quick. But she loves to talk and is a natural mimic, taking off her formidable mother, her suffering daughters, the snooty doctors, the gushing chat-show hosts. Her home is small, cosy and crowded. She lives with her second husband, Bob, a salesman whom she married 20 years ago. Her Akita puppy, Rupert, who at five months old probably weighs more than either of her daughters at their deaths, pads furrily about. The walls are covered with her own paintings; there is a knick-knack on every surface, many of them salvaged from Samantha's now-empty council flat.

"This was Samantha's, and this, and this," she says, pointing out a vase of pink silk flowers, a ceramic candle-holder and a statuette of two roly- poly children in the snow - a souvenir of Samantha's stay in Canada. As well as painting, Suzy also moulds decorative plaques and fridge magnets from salt-dough; her kitchen is hung with representations of food, her fridge covered with magnetic miniature burgers, the walls hung with varnished fruits. Some of these she gave to Samantha, as if to encourage her to eat; now she has them all back again, filling every surface of her house to overflowing.

WHAT CAN have led the Kendall twins to take their own lives in such an ugly way? Their mother has no idea. She readily admits they did not have an ideal start in life. "I got married against everyone's wishes, when I was 19," she says. "The family didn't like him, but I thought he was the bee's knees, I thought he was wonderful. I was besotted with him." Suzy worked in a petrol station to support her husband, who had no job; they lived in a succession of small rented flats in Birmingham. Then she missed a pill and by the time she went to the doctor, thinking she had a stomach bug, she was already four and a half months pregnant. By this time she and her husband were already arguing; he would disappear for the day, while she worked selling petrol and valeting cars.

"When the doctor told me I was pregnant, I was inconsolable," she recalls. "We hadn't planned a child. He wasn't working, and I thought I couldn't keep working if I had a baby." There were rows and reconciliations; Suzy got as far as filing for divorce at one stage. "My mother was furious and wanted to wash her hands of me. She said she would help to bring up the baby, I didn't need to be with him," she says. Then her husband went to prison for nine months for burglary; it was her mother who was by her side when she gave birth to not one but two daughters: Samantha first, then 10 minutes later Michaela, on 12 May 1967.

Everyone, including Suzy herself, was stunned by the surprise double-birth. Her own mother was not impressed. "Mum didn't blame me as such - it was something beyond my control - but she did say, 'Why on earth did you have to have twins? How are we going to manage?' " Suzy recalls. "On the third of June, my husband came out of prison. We tried to live together in Mum's house, but it didn't work out."

More rows, more reconciliations. He thumped her; cash was tight. Two babies were hard work. "I was inexperienced, I'd never had anything to do with children - I was scared of them. I'd never even babysat before. He left me for another woman when the twins were two and a half. I hadn't any money, I hadn't any prospects. I was hysterical. I thought my whole world had fallen apart, I couldn't bear it. I was still in love with him, I just didn't know what to do."

She gathered up the twins the morning he left and went round to her mother's house. "I was in bits, and she started clapping her hands and saying, 'Good, good! You're better off without him.' Then she came up with this idea. She said, 'You've got no money, you have got to go out to work.' She said she would give up her job and bring up the twins and I would pay her. I moved in just round the corner from Mum and Dad so I could see them - there just wasn't room in the house for me to move in there permanently." Her mother, she says, was an authoritative figure. "Mum was a matriarch. What she said to do, you did. In retrospect, if I'd insisted and said I was going to bring them up myself, who knows what would have happened?"

So Suzy went out and found a job driving Transit vans. A number of children in the twins' class at school were being brought up by their grandparents, she says. "People assume the mother was up to no good when that happens, but there were a few kids in their class who were in the same position, due to different circumstances. I believed my mother knew best. When we had disputes about the twins, she would say, 'What do you know?' And I believed her - she'd brought up three daughters already, after all."

Suzy's mother, the twins' grandmother, had cooked for a living; she worked in the canteen at the GPO. "Mum was always cooking, so the twins did pile on the weight," recalls Suzy. "If the girls were ever sick or ill when they were young, she'd make sure they got a good meal inside them. They'd comfort-eat as well, back then. I remember when my sister came from London and my mother met her off the train with the twins. And they always remembered this: my sister got off the train and said, 'Oh my god, Mum, they're enormous' - and they heard. They said to me they were so upset that on the way home they got a half-pound bar of chocolate each and ate the lot."

By the age of 14, Suzy estimates the twins weighed around 14 stone each - she refers to them as "well-covered". At the time, she was working as a singer; despite their weight, the twins had the confidence to get up on stage with her in clubs and pubs round Birmingham, and both hoped for a musical career. Neither shone academically. They hated school because of all the taunts," says their mother. "They said they weren't accepted because they were fat. One boy called Michaela a fat blob and she hit him - they both got detention for that."

And then they decided to do something about their weight. Michaela and Samantha started dieting over the school summer holidays, the year they were 14. "Every time I went round there, they'd be sitting there with just an apple. My Mum said they were driving her mad." Back in the early Eighties, awareness of anorexia was nowhere near as widespread as it is now - particularly not on a Birmingham council estate. Suzy had no idea what she was dealing with, as the twins each lost several stone over the summer break. At first she was concerned, but not unduly so. "Then I realised this was not just dieting, this was starvation. They'd go to the chemist and get a bar called 'Crunch and Slim' and they'd ration themselves to one of those a day. They'd have a bit of yoghurt,or an apple between them, or a bag of crisps, but only eat two crisps and throw the rest in the bin."

The twins' grandmother couldn't cope; Suzy tried to do what she could. "We'd sit and talk about it for hours and hours and hours. They'd say they realised they were being extreme, and promise they wouldn't do it any more. They promised and promised, tomorrow we'll have a proper meal. But they never did."

By the end of the summer, Suzy was sufficiently worried to take the girls to the family GP, who, she says, was baffled. "He just didn't know what to do." And so began a long round of doctors, professors, psychiatrists. At first, she believed that one of them would be able to help, but gradually her faith in the medical profession was eroded. "I was brought up to believe these people were my superiors, and to treat them with respect. But nobody seemed to know what to do. There was one professor who thought he knew it all - he was about as useful as a chocolate teapot. When Michaela was sectioned, he treated her for eight months in hospital. When she got the section lifted, she came home and died within two months. It was the same with Samantha. I went with her to his office. Sam said, 'Oh, but I'm eating now, professor,' and he said, 'Oh good, well that's all right then. Make sure you keep it up'. But she was lying between her teeth. She wasn't eating. I knew."

In their late teens, the twins were still managing to cling to some semblance of normality in their daily lives. After leaving school, they managed to get jobs and each started a steady relationship and lived with her boyfriend. But they were growing sicker, and both were in and out of hospital. In the first interview published with the twins, in the Sunday Mirror in 1993, Michaela said they both became pregnant when they were 22. If they had continued with their pregnancies, perhaps their lives would have been different. But, said Michaela, "We looked in the mirror at the same time in our separate homes and thought, 'We're going to get fat.' So we decided to have abortions."

"They couldn't stick to any jobs," says Suzy. "They were Bluecoats and Redcoats in holiday camps, but they were told to leave because of the way they looked. In the end, the manager of the camp where they were working then, told them they were popular and everything, but the guests were appalled by having to sit with them over breakfast - they were putting people off their food. They were thrown out of cafes too."

In 1992, after a five-year relationship, Michaela's boyfriend gave her an ultimatum: the anorexia or the relationship. "I told him it had to be the anorexia," she said. She went back to her grandmother's house, and Samantha packed up, left her own boyfriend, and went to join her. It was a fatal move. The two encouraged each other - before Michaela was eventually sectioned, Samantha was telling another tabloid interviewer that their daily diet was a couple of extra-strong mints at midday, a couple of crisps mid- afternoon, and an evening meal of a quarter of a slice of Slimcea bread and a sliver of black pudding. Samantha was able to see how thin her sister was, even if she couldn't relate it to her own body. She said: "The competition makes it twice as bad. If Michaela says she doesn't want a cup of tea, then I won't have one, even if I'm desperate. When I say to her, 'Please, Michaela, eat a bit more, you look like a skeleton,' she snaps back at me, 'You're only jealous'."

After eight months in hospital, during which time she fought against forced-feeding, Michaela appealed against her sectioning and was allowed home; she died next to Samantha a few weeks later in the double bed they shared, weighing four and a half stone.

At this point, in desperation, with one daughter already dead, and the other dying, Suzy wrote to Chat, a women's magazine that pays readers for their true-life stories. "I wrote to Chat, because no one was listening to me. Doctors were failing me, psychiatrists were failing me - the twins' own doctor didn't know how to handle it. It was a maze I couldn't get out of. I had to do something, there was nobody else. My mother was too old and she was ill herself - she's had two strokes. And that's how it all began."

She was taken aback but initially hopeful when the story was picked up internationally. "The Chat article opened up a whole storyline all over the world. But I didn't mean all this publicity to happen, I wouldn't have wanted it. What I was hoping for was someone who could come forward and cure Samantha. People are cruel, they say, 'She's doing this for publicity,' but that's nothing to do with it. The people out there haven't got a clue. It's no good judging me. I don't need judging."

SUZY KENDALL might have made some wrong decisions, but if that is the case, she has paid for them many times over. Anorexia changes people both physically and mentally, and anorectics are not easy to get on with. As well as becoming thin and weak, chronic anorectics often grow a coat of downy hair on their skins; their teeth are ruined by vomiting. Constant, large doses of laxatives, self-administered to purge food from their bodies, can stop them controlling their bowels. Starving can also wreck the personality. Samantha, says Suzy, used to be a joker, "a bit of a Lily Savage". She was also generous. "If you admired something of hers, she'd give it to you - her earrings, her jacket. She was very giving and kind."

But her condition changed her. "Anorectics become devious, like a junkie, not to be trusted. They are not the girls you knew. I went with Samantha to New York; we were on Maury Povich. Sam wanted to look round the shops, so we found ourselves in this store that sold paste jewellery. Sam loved jewellery, and we decided we'd buy little gifts for the people back home. So I'd got some things in my little wire basket and Sam had some in hers. Then all of a sudden, a great big diamante necklace dropped out of her sleeve."

The owner of the shop came raging over as more jewellery fell out of Samantha's sleeves. "I just didn't understand, because she had the money on her to pay for everything. The owner took us to the cash desk and made us pay for everything, or he'd call the police - half the stuff she didn't even want or like. To make matters worse, she was on big doses of laxatives. When we got out she was shaking like a leaf ... she'd had an accident. She said, 'Oh Mum, I've bobbied myself' - that was the word we always used - 'I've got to go back to the hotel'. I was so angry with her, I said, 'You can go back by yourself, I've got to go and walk about and calm down.' "

After her appearance on American TV, Samantha went to the Montreux Counselling Clinic in Canada, in the summer of 1994. Her mother was hopeful; she still believes the Canadian method, which involves initial 24-hour one-to-one care and intensive counselling, is a model that should be adopted here. Samantha put on weight, and gave a series of interviews in which she talked about her "cure". She even spoke of becoming a counsellor herself, and helping other anorectics. "Mum, you will be so proud of me when you see me," she wrote in a letter home. "I'm still determined to never starve myself again. It killed my darling Michaela, it's not killing me."

Then Suzy went over to visit her for two weeks. "I could see the problem was still there, and then out of the blue, she said, 'Mum, I'm coming home with you.' I said, 'No,' but she said, 'If you leave me here I'll die.' She was isolated, her twin was dead, she didn't know anyone. Everyone was thinking: 'She's had all that money spent on her, she should be getting well.' But there was one thing missing - her twin. Nobody could do anything about that."

Samantha came home, against Suzy's wishes, and announced in another interview that she was tired of being "wheeled out like a circus freak" to publicise the Canadian clinic's success. She admitted that she had continued to take laxatives while being treated. "Because I was a high-profile patient, I knew that it would reflect on the clinic if I didn't appear to be responding," she said. "I knew I was good for attracting other fee-paying patients. Everybody wants to be able to say, 'I got Samantha Kendall better'."

Sadly, she was far from better. "But she was 27 years old and I couldn't dictate to her," says Suzy. "She insisted that she needed to come home. She said, 'I can't wait to see the Yew Tree shopping centre' - it's our local shopping centre. I said, 'You're surrounded by mountains and blue sea and you want to see the bloody Yew Tree!' But she came home, and she lived here with me and Bob for 12 months. I tried to persuade her to go back, but once a Taurean's mind is made up, they don't budge." Bob's sales job took him out on the road a lot, and when he was away Samantha slept in her mother's bed. "She insisted on sleeping with me, she said she felt safe. But I knew she was back on laxatives because of the sheet the next morning - Bob used to go mad."

Suzy's second husband Bob, a patient and kindly man who has been, she says, more of a father to the girls than their natural one, was by now reaching the end of his tether. Their son, born when the twins were just starting their illness, also suffered, becoming hyperactive and difficult as a child. He has since left home.

Samantha went back into hospital towards the end of 1995, a year after leaving Canada. "She was there for four months, in a medical ward - one for physically ill people, no place for someone with her condition," says her mother bitterly. "I went on and on about it to them, but they said, 'Oh, we have to get the body right first.' They were doing everything arse-about-face, I knew that it's the mind you have to sort out. They said I didn't know enough to give them orders. I wasn't giving orders, but I knew they were wrong."

Samantha had other problems as well. "She was allowed out of the building and out of the grounds - she just went back there to sleep," says Suzy. "And by now she was drinking too. They called me at 4am one morning and said get over here, Sam's dying. When I went over I knew she'd been drinking - she was going out and buying it. The hospital's attitude was just, 'Leave Samantha alone, she'll get better.' I went to see her every single day. Our marriage was in jeopardy - I spent more time with her than with Bob."

This, she says, was one reason that Samantha elected to move back not to the family home but into a nearby council flat, alone. "She made me promise I'd say she was homeless," says Suzy in a small voice. Up to now, she has kept her composure; anger has carried her through, but now she is close to tears. "She said she wanted her own independence, a flat of her own. She said, 'I know what I'm doing to you and Bob. If I come back and live with you it will all start all over again.' I told her to come back to us, but she said she wouldn't live far away, so I agreed. The council offered her a wonderful flat." Suzy helped Samantha decorate, painting a seascape and fluffy pink clouds on the walls.

Samantha then started to refuse all help. Suzy visited every day and tried to persuade her to come back home. "Some days she wanted to live. But other days she'd say, 'I don't want to be here. Why don't you all leave me to die. If you leave me here I'll be able to drift away into oblivion.' " The medical health officer assigned to her case tried to persuade her to at least go and stay with her mother for a while, where she would be looked after, but she refused. It became clear that her condition was worsening dramatically, and eventually, this summer at the beginning of July, she was sectioned by her medical health worker, and put first into a medical ward. When Suzy next saw her daughter, she was semi-conscious. "She had two drips in each arm and a feeding tube in her nose, and she was slurring her speech as if she was drunk. She went into convulsions, her eyes were rolling back in their sockets ... "

Samantha was then moved to a psychiatric unit. "It's a posh name for a nut house. They sent her there against my wishes and they didn't even tell me they had moved her - when I rang the first hospital she'd been in, they said, 'Sam's not here any more,' and I thought she'd died. When I went to see her, she was in tears, she was out of it, she was clinging to me. She thought they were going to kill her, and that they were making blue films about her. She said I was an actress, and Bob was an actor, and we were all out to destroy her. She was in with schizophrenics, drug addicts, raving alcoholics throwing the furniture about. She was terrified. One night there was fighting and screaming, the police were called and all the staff were running around with blood on their clothes - she didn't know why."

Suzy and Bob consulted a solicitor, to try and obtain Samantha's release, and the sectioning was lifted on 25 September. Samantha died on 20 October . "When she came out she was completely mental," says Suzy. "I couldn't have the radio or TV on, because she said they were planning her death. I had tried to cope with the anorexia, but I couldn't stand the mental disorder. I couldn't cope with it. It was the same with Michaela - all the same mistakes." And she weeps.

Samantha went into her final coma at Suzy's house, where she spent the last week of her life. She said that Michaela had appeared to her and she was ready to die. Suzy says they later discovered bottles and wrappings that suggested she had taken an overdose of paracetamol, to which she was allergic. The night before she died, Samantha ate half a kebab and gave the other half to Rupert, Suzy and Bob's Akita puppy. Rupert and Samantha were both violently sick in the night but Suzy put it down to food poisoning rather than anything more serious. "I felt terrible. The paramedic told me off - he said, 'Why the bloody hell have you left it this long to call, she's in a coma.' I didn't realise. She was always so lethargic and tired. They put her on a life-support machine but I think she was already gone."

Suzy Kendall believes that, with hindsight, Samantha was doomed when Michaela died. "She had to suffer for three years and six months before she joined her. She missed her twin so much she didn't want to live without her. Twins have a real uncanny bond, and it's so strong. They aren't like ordinary siblings. You can call me a loony, but Michaela came for Samantha. They are together now. No one ever split them up."

Her life, and the lives of her husband and son, have been poisoned by anorexia for the past 15 years. And although she denies any guilt, she does say, sadly, "I can't do anything right. I'm a real Calamity Jane." What will she do now? She intends to campaign for further recognition of anorexia. But it's difficult to see exactly what she would like to achieve. "The government should do something," she says vehemently. But what?

And she is tired. This is the end of a long effort. "I deserve some sort of solace and peace now. I won't get away unscathed from this, I won't make old bones. But I don't care any more. There is nothing as bad as this that can happen."

Suzy Kendall's role in her daughters' lives and deaths is one that fascinates people. "Why didn't their mother make them eat?" is a question that comes up over and over again. "Why didn't she make the doctors do something?" But making someone eat is not easy. At one point, Suzy was physically holding Samantha's jaws together to try to stop her bringing up the food that would have saved her; how was she to make her daughter eat - physically hold her down and force food down her throat? I am the same age to within a few weeks as the Kendall twins would have

been, had they lived. Among my close friends are two recovered bulimics, one recovered anorexic (she now sweats it out at the gym every week) and half a dozen others who have been on a diet of one kind or another since their teens. I am very glad that none of us ever strayed so far down that slippery road that we could not or would not come back; because, whatever one may think of Suzy Kendall and the others responsible for the twins' care, if a young woman decides categorically that she is going to starve, there seems to be very little that anyone can do. The twins in happier times: by their early teens, Samantha and Michaela were being teased for being too fat

Michaela and Samantha started to diet when they were 14. By her death, Michaela weighed less than five stone

The twins in 1993, shortly before Michaela's death: 'The government should do something,' says Suzi. But what?"

Link: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/in-anger-as-much-as-sorrow-1294373.html

Follow on Buzz

UPDATE

UPDATE