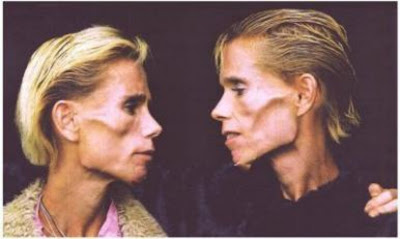

This news of the Wallmeyer twins made headlines in July of 2004:

"Last Chance for Twins

Twin sisters starving themselves to death may be jailed in an attempt to force them to turn their lives around"

"Geelong twins Clare and Rachel Wallmeyer both suffer severe anorexia, barely surviving on a diet of little more than snacks, energy drinks and laxatives.

The emaciated sisters, perfectionists who studied biomedical science and physical education at university, are also compulsive long-distance runners.

They have wasted away for two decades, at times slipping to 28 kg.

Though only 34, their bodies have started to break down.

They are shrinking and they have the bone structure of women aged 70 to 100.

But the siblings also have a history of criminal offences and drug use, believed to be linked to their psychological disorder.

Clare was this week sentenced to two months' jail for a series of thefts.

"It's just right out of any sort of control. She continues to want to injure herself," he said.

Mr von Einem said Clare's anorexia, drug addiction and continual lies were a tragic combination.

"Sadly and unfortunately, she is going to have to be treated within the prison system for a short term," he said.

But Clare, who threatened to completely stop eating if locked up, was given a temporary reprieve and released on bail while she appeals against the jail term.

Sister Rachel also faces criminal charges in the coming months for drug-driving, heroin use and an assault in which she allegedly pushed a victim on to train tracks.

The twins both developed severe eating disorders in their early teens.

They became addicted to running and trained constantly for marathons.

They kept running until both recently suffered stress fractures in their feet.

The twins are inseparable. In 1996, when Rachel was so ill she was admitted to a psychiatric unit at Royal Melbourne Hospital, Clare voluntarily admitted herself too.

Rachel last night told the Herald Sun of her sense of hopelessness and loss of self-esteem.

"No one understands the disease until they have lived it. It's like the Grim Reaper, a black hole in your soul," Rachel said.

"Our bodies have deteriorated to a level where they are damaged...it's a terrible disease, but it's not a choice.

"We don't feel like we've got anything much to give the world. We feel we are a burden.

"We don't feel we are special to anyone, except to our family."

Parents Bob and Moya told of the heartbreak of watching their daughters slowly die.

The couple check the twins' beds every night, fearing they will succumb to their disorder or die of an overdose.

Moya said her daughters, born eight weeks premature, were diagnosed anorexic at 14.

"They were girls who were good at everything. They did very well at school, were good at music and athletics," Moya said.

"They are intelligent and sensitive, but they don't like the world the way it is.

"I think the anorexia is their way of not wanting to cope with it."

A police source said the courts had tried to give the twins every opportunity to reform, but repeated offending and an inability to change left prison the final option.

"At the end of the day it's the only thing left. Everything has been tried," the source said.

"They didn't want to have to come to this, but it was actually the very last resort (for Clare)."

Previously, the twins have been directed to counsellors and specialists for their disorder and drug problems, without success.

"Many people have tried to help our girls, but they eventually get put in the too-hard basket," Moya said.

"My doctor said they don't know what to do.

"But you don't give up on your kids. You just keep going."

In 2004, Clare had the bone density of a 72-year-old and weighed only 58 pounds, and Rachel, the bone density of a 100-year-old and weighed 48 pounds.

To provide some background, the following is a transcript of Peter Overton's interview with the Wallmeyer twins and their parents, Bob and Moya Wallmeyer, on 60 Minutes (Australia) on October 31, 2004:

"What a waste"

"Rachel and Clare Wallmeyer are identical twins. They were beautiful, bright straight A students. Then, when they were 14, their perfect world collapsed. Kilo by kilo, the twins began wasting away.

They still live together and still share everything, including — tragically — a death wish. Quite simply, they've given up on life. But, thank goodness not every one has given up on them.

PETER OVERTON: Identical twins Clare and Rachel Wallmeyer are running out of time. Their lives have been ruined by anorexia and now they're literally starving themselves to death.

CLARE WALLMEYER: We are living solely anorexia and to live solely anorexia...

RACHEL WALLMEYER: …is horror.

CLARE WALLMEYER: …is horror.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: We live to die... We, we...

CLARE WALLMEYER: To be in constant pain, to wake up every day and not ... sometimes you can't get out of bed, you're just so tired.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: Everything is a struggle. And there's no point in it.

PETER OVERTON: Rachel and Clare run to lose weight. This obsessive training is all part of their illness, an illness they've been fighting for 20 years.

Rachel, how much do you weigh?

RACHEL WALLMEYER: About 32.5 kg, just off.

PETER OVERTON: And what does 32.5 kg, that number, mean to you?

RACHEL WALLMEYER: I'm lower than I was, so the less, the better, I guess.

PETER OVERTON: Clare is one kilo heavier.

CLARE WALLMEYER: So we get on the scale hoping we're less...

RACHEL WALLMEYER: So we're heading the right way.

MOYA WALLMEYER: They were happy, vivacious, very affectionate mischievous, um, beautiful, very lovable.

PETER OVERTON: Rachel and Clare grew up in Melbourne. They did well at school and excelled at sport. For their parents, Bob and Moya, the twins girls had a bright future.

BOB WALLMEYER: Golden, golden girls.

PETER OVERTON: And how would you describe them now?

BOB WALLMEYER: Ill, very ill. Maybe they're going to die.

PETER OVERTON: Teenage girls are most at risk of getting anorexia and Rachel and Clare were 14 when their weight dropped to a pitiful 28kg. It was 1984.

MOYA WALLMEYER: I picked up a diary that was open in their room and read that they had read about anorexia and they had stopped eating...

BOB WALLMEYER: And were being noticed.

MOYA WALLMEYER: Yep. That was their way of being noticed at school.

CLARE WALLMEYER: When we got anorexia, it was the first time that we got recognised. People actually verbally said to us, "Oh, gee, you've lost weight," and we thought, "Hey, this is an achievement here."

PETER OVERTON: When Rachel and Clare look in the mirror, they don't see what we see.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Your face is thinner.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: No way. You are so much thinner.

CLARE WALLMEYER: You've got muscles, train legs. I'm all flab.

PETER OVERTON: They see a distorted image of themselves and each other. Anorexia is not just about being thin. It's a serious mental illness.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: I think the biggest lesson that we could teach people is anorexia is an insidious disease, a mental disease that has physical implications that kill and those that suffer it, unless they have something to fight for, die.

CLARE WALLMEYER: You take away the anorexia, then, and, my God, I'm nothing. I don't even know who I am now.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: We've lost ourselves, but we never found ourselves in the first place, I don't think.

MOYA WALLMEYER: People say to us, "You're so strong. How come you're so strong?" And we say, we think to ourselves, "You want to see me at night when I'm crying all night."

BOB WALLMEYER: That's very, very frequent.

MOYA WALLMEYER: That's why the garden is so green.

PETER OVERTON: What, from your tears?

MOYA WALLMEYER: (Nods)

PETER OVERTON: How bad has your body become, Clare?

CLARE WALLMEYER: I've had 38 stress fractures because my bone density is well over that of a 100-year-old. I've never menstruated. My liver function is down, kidney function is down.

PETER OVERTON: Over the past 20 years, their parents have desperately sought the advice of doctors, psychiatrists and counsellors. But for every occasional breakthrough, there has always been the inevitable relapse.

BOB WALLMEYER: We can't understand why the one who's feeling better can't pull up the one who's down. It seems to work the other way, mostly.

PETER OVERTON: Their daughters are now 34 and more fragile than ever. They've been admitted to hospital more than 40 times and have attempted suicide on numerous occasions.

Give me a sense of what you eat, if you eat anything, in a day.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Um ... essentially, we don't eat anything. We might have a piece of watermelon.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: And Diet Coke we have and coffee.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Coffee.

PETER OVERTON: And do you use laxatives as well?

RACHEL WALLMEYER: At least 20.

PETER OVERTON: You have so much strength and control not to eat. Why can't you harness that strength to eat?

CLARE WALLMEYER: Why? What for?

RACHEL WALLMEYER: What do I need to eat for?

PETER OVERTON: Does anything in life give you pleasure?

CLARE WALLMEYER: No.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: A hug.

CLARE WALLMEYER: A hug from my sister.

BRONTE CULLIS: It's a serious psychological illness. It is not a physical illness, but society sees it as purely an aesthetic thing and a choice thing and this is not a choice. Why would these girls … why would anyone want to live like that?

PETER OVERTON: If anyone can offer hope, it's Bronte Cullis. Ten years ago, she was in the grip of this appalling disease. It took years of intensive treatment, but Bronte was able to beat anorexia. Today, she's one of the few people who truly understand what Rachel and Clare are going through.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Still that doesn't change the fact that there's no-one here at this point in our lives that understands Rachel and Clare.

PETER OVERTON: When you see Rachel and Clare, too much?

BRONTE CULLIS: Can we not do this?

PETER OVERTON: Yeah, it's too much, isn't it?

BRONTE CULLIS: I'm so sad that they can't see any hope, because I've been there, but I am here now and I know that life is worth living and I wish so much I could make them see that. But I can't. And that's a very frustrating thing, that you can't make somebody want to get better, that they have to want it for themselves.

PETER OVERTON: But right now, they want only for this to end. They've made a pact to get down to 25kg. Then they believe they'll die.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: I think over the past three and a half years, my soul and that light that I might find someone or something to beat my disease with has gone.

CLARE WALLMEYER: And I haven't, Rach.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: And Clare's the only person that remains by my side. And at least we'll die together.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Being with Rachel ... makes it somewhat easier to die.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: There will be a life afterwards or something where I can give to the world and be somebody.

CLARE WALLMEYER: She's someone to me.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: And she's someone to me.

PETER OVERTON: They've never finished university, never had a job, never been in love. They have but one friend. Tim Cowen is a community worker with the Salvation Army in Geelong. His visits and gifts provide laughter and joy to lives that have so little. Sadly, this year Rachel and Clare's plight became even more desperate. In an effort to lose extra weight and to block out the pain, the girls turned to amphetamines and other hard drugs. Their drug use led to crime, including petty theft, and now they're both facing possible prison sentences.

What could happen to you both, do you see, if you do go to jail?

CLARE WALLMEYER: We'll die.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: Quicker.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Quicker.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: And we feel we've got such little time left. To take that away...

CLARE WALLMEYER: To be punished...

RACHEL WALLMEYER: …and separate us when we've got such little time.

CLARE WALLMEYER: We regret so much what we've done.

PETER OVERTON: Society judges them really harshly. They call them criminals and drug addicts.

BRONTE CULLIS: They are a manifestation of their illness. It is what their illness does to them, makes them do because they are so tortured inside. And I just think it's so terribly sad that any person with mental illness, whatever mental illness it is, is judged so harshly.

PETER OVERTON: After years of living with her daughter's illness, Jan Cullis now runs the Bronte Foundation, which treats anorexia. Today, Bob and Moya have brought the twins to be assessed for possible treatment.

JAN CULLIS: Let's talk a little bit about how you think Mum and Dad would be if you weren't here any more.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: I think they'd probably go through the mourning processes. They'd be devastated at first. But the world keeps turning.

JAN CULLIS: Okay, what you're doing right now is you're intellectualising what Mum is going to feel.

MOYA WALLMEYER: I just cannot imagine losing them. (Sobs) I think it would be horrific losing one daughter, but losing two — I can't bear to think of it. They've been fighters all their lives. They were born eight weeks prematurely and they had to fight then...

JAN CULLIS: When I first saw them, my heart sank, because they're in a really desperate place. But as you talk to them, you realise that in some very small way, they are still there inside. And there is a tiny part of them that actually does want to make it.

CLARE WALLMEYER: I came in here completely black inside. Part of me is there's someone that's switched a light on and maybe, just maybe, Rachel and me can get together and show the world how strong we can be. Maybe, you know, this could be the start of it, rather than the end of it like we planned.

RACHEL WALLMEYER: But can you imagine tomorrow getting up in the morning and having breakfast?

PETER OVERTON: Are you still shocked when you see young women like Rachel and Clare?

JAN CULLIS: I don't get shocked any more. I'm just so deeply saddened that as a society we still walk away from people and give up on them so easily and I cannot imagine where has the support been that has allowed these people to reach this point?

PETER OVERTON: There's no guarantee of a happy ending for Rachel and Clare, nor is there much time left. But while there is time, there's hope.

MOYA WALLMEYER: I get angry when people tell me they're going to die. I'll cope with that if the time comes, but no, I've fought this illness for 20 years and I'm not going to stop fighting.

CLARE WALLMEYER: Most people have a mark to leave on the world and we haven't. All we leave is failure, yeah.

PETER OVERTON: Perhaps the mark you could leave on the world is success: "We got better, we beat it."

RACHEL WALLMEYER: Maybe. But people still judge the disease, don't they. But maybe the best lesson that anyone could learn is that anorexia kills. It's not a choice.

CLARE WALLMEYER: It's not an achievement to be thin.

PETER OVERTON: Do you have hope for them?

JAN CULLIS: I have hope for everybody with this illness. I don't think I could front up to work every day unless I had hope. because it would be too sad. I think the chances for them are really, really tiny. But I think it really comes down to the absolute desire to live over the easier way to die and if they can find a desire to live within them, then there is a chance that they can beat this."

In 2005, the Wallmeyer twins got in trouble with the law. Clare received a two-month jail term for stealing chewing gum, a soft drink and a blender. Rachel received a 21-month suspended jail sentence for driving offenses, theft and for pushing a man who she said insulted her off a railway platform.

Earlier, in 2003, Rachel was involved in a police chase through the city of Geelong when she ran a red light and lost control of her car. She was also charged with injecting heroin in public.

In October of 2005, a judge released the twins without recording convictions and dismissed all charges against the twins except for those for which they had already paid the fines.

On November 4, 2006, The Sydney Morning Herald published an interview with the Wallmeyer twins. Here are portions of that interview:

"Twin sisters Rachel and Clare Wallmeyer, 36, have had anorexia for 22 years. Six years ago the would-be athletes moved from Melbourne to Geelong with their parents. They now share a flat, living on disability pensions.

Rachel: We've always been slight. We were born prem and put straight into the humidicrib because we weighed so little. No one was allowed to touch us. They tried to separate us in grade prep but we wouldn't let them. We sat in the same classes at school, and at uni we started the same degrees together...We were naturals at running, esp Clare. I did more swimming. I'd do 3 hours' swimming and an hour's running [a day] and she'd do an hour's swimming and about 3 hours' running. We didn't actually compete much. We trained to be fit.

I've gone down the trail of anorexia a bit more than Clare. When they put me in hospital the first time, Clare told them, "Let me in with Rachel or I'll curl up on a bench outside until she's out." So they admitted her, too.

I've always seen Clare as a pink rose, just waiting for a right person to make it blossom. I was a black rose with black thorns that pricked everybody. I hate myself and by making myself smaller there is less of me to hate. Clare hates herself, too, but I find that tragic because she's soft and beautiful and I adore her. I want to be as thin as Clare. If my sister says, "I'm going to lose weight", then I say, "I'm going to lose weight, too."

People say, "Get better, get better." What is better? Anorexia has become a big part of our identity and I have surrended to that. Whatever happens, happens. My sense of balance is gone, I've got severe osteoporosis and my brain and my heart have shrunk. We're scared of dying but we're also scared of living the way we do. If I died, Clare wouldn't live a minute past me and I'd do the same for her. We once made a pact to get down to 25 kg so we could die together and slip over the rainbow with Grandma.

Grandma was 93 and had dementia but she always called us her beautiful granddaughters. People said we looked a lot like her. When she died I swam the two hardest kays of my life and then I went off to a park with a box of Panadiene Forte and tried to [commit] suicide. Everything got on top of me because we'd moved to Geelong and I hated Geelong. I was in and out of hospital and my weight dropped down to what it is now, 30 kg. I lost the ability to train which saw me try about 20 OD's in the last 4 years. Clare had a few [suicide attempts] too, but she kept running and running and running, so she was okay. She's more a confident personality. She made friends in Geelong and didn't want me around any more. Then she got injured and lost her training and we moved into a unit together. Now we're closer than we've ever been. We've probably become too close but not too close for me. It's like we're back in the humidicrib sometimes, Clare and me together, watching the world revolving ard us.

Clare: Our days are very much the same because we don't have our training any more. We sleep in [single] beds side by side but lately Rachel's been waking up in my bed, because it's been cold and her blanket hasn't been working. Often Rachel will have been up half the night cleaning. The flat continually collects dust and we're perfectionists who like to clean everything as soon as we've used it.

We start the day with a shower and a cigarette. Breaky is the same as lunch and dinner: some melon and a cup of coffee, if we manage to keep that down. We each put 10 artificial sweeteners in our coffee. Everything we eat and do has to be exactly the same. If I walk a k, she'll walk a k. It's not a competition, it's more of non-competition because we want to be identical. Rachel uses my toothbrush, she buys the same clothes.

Everyday we walk four kays into town to get our medication [methadone] for the pain of our osteoporosis. [Although the girls have experimented with heroin, and Rachel dabbled briefly in petty crime, they were never addicts.] Then we'll walk home or go to Mum and Dad's, which adds about 5 kays to our walk. We live in a bad area where people yell out of cars, like, "Eat, ya fatso!", so we don't walk there. We just walk out of there. Also we get desperately lonely at home. Rachel and I don't talk because we always know what the other is thinking.

Rachel used to be the more vivacious twin. Ive always been the leader. I'd wait for Rachel at school and I learnt to write before her, to swim before her, but everything I achieved I'd hide from her until she got up to my level. It would upset her too much to see me ahead.

Running was my freedom. I'd run 40, 60 kays, up into hills, get lost, often at night - I loved it so much. Now all I've got left is my anorexia, the only thing that can make people care about me. Of course our parents care about us, but they think I'm the person I was before I got anorexia, the one who got straight As and played netball. But Im not. I don't know who I am and that's very scary.

The only thing I can control about my life is my weight. Some might say that's a weakness, and it is, but it's also a fortitude. Beforehand people might say I was a fantastic athlete; at least now people can see I'm a fantastic dieter.

Rachel and I both found moving to Geelong very hard. She loved her swimming, the regimented nature of it, lap after lap. Everyday she would travel back to the same pool in Melbourne. I trained in Geelong but I got one stress fracture after another. I'd come home from a run, go to my room and put a bookcase up against my door. I shut Rachel out beause she loved everything of mine and she'd just take it because she loved to copy me. Rachel figured I must be happy doing my own thing. She had like a nervous breakdown. She stopped training and was admitted to hospital so many times that they took away her smile.

I think Rachel being the way she was stopped me from being happy in Geelong. Not that I blamed her. It is my choice to like her so much, to feel she is so important to me that I'd give up my life for her. When she gives me a hug, two halves come together as one."

~~~~~~~~~~

The Wallmeyer twins' criminal behaviour continued in 2007, as reported in The Geelong Advertiser:

"Rachel and Clare Wallmeyer Anorexia 'no excuse' for drug dealing

Karen Matthews

18Aug07

ANOREXIA was no excuse for drug-trafficking or other criminal behaviour, Geelong Magistrate Michael Coghlan told twins Rachel and Clare Wallmeyer yesterday.

"Nor can you continue to rely on your condition (anorexia) to keep you out of jail,'' he said.

"You are no different to any other person with a psychiatric condition coming before the courts.''

Mr Coghlan said the pair had many prior court appearances for dishonesty and drug-related offences.

"In my opinion you have been treated extremely leniently in the past and given sentences on a lower scale to others of similar offending,'' he said.

"At what stage does your condition stop becoming an excuse?''

The Wallmeyers, aged 37, pleaded guilty in Geelong Magistrates' Court yesterday to charges of trafficking steroids and possessing amphetamine.

Police Prosecutor, Senior Constable Geoff Lamb, said that in November last year, police were conducting undercover drug operation `Thornbirds' in Geelong.

He said a telephone intercept picked up the Wallmeyers purchasing varying amounts of amphetamine ranging in price from $50 to $200, often on a daily basis.

"The male suspect would deliver the amphetamine to the women at their flat and this continued until May this year,'' he said.

"It was also found that the Wallmeyers had attended various medical practices and obtained prescriptions for 33 vials of steroids as part of a health program to help them put on weight.

"Instead they either sold or swapped the steroids in return for amphetamine.''

Sen-Constable Lamb said an undercover police officer attended the Wallmeyers' flat on three separate occasions in January and purchased six vials of testosterone from the sisters for $125 each.

David Cronin, for Rachel and Clare Wallmeyer, said his clients had suffered with anorexia for 23 years and that the pair used amphetamine as part of their illness _ so they could push their bodies.

He said both women had played a relatively small part in the drug ring and had not sold drugs to make money but to feed their own habits.

Mr Cronin said that only in the last two years had the women been properly treated for their anorexia and that jail would have a detrimental effect on them.

Mr Coghlan asked Mr Cronin at what stage did he feel his clients would be ready to face up to their responsibilities and stop relying on their illness to escape the consequences of their criminal activities.

"Let's say we feel sorry for them and yes, they need treatment,'' Mr Coghlan said.

"At what stage does it stop becoming an excuse? Drug trafficking is one of the most serious of offences. Enough is enough.''

Rachel and Clare Wallmeyer were both convicted and sentenced to two months jail wholly suspended for 12 months. They were also placed on 12-month good behaviour bonds."

~~~~~~~~~~

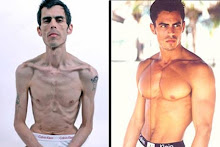

It is apparent from the above photo that Rachel and Clare had gained weight by 2007...thankfully.

The Wallmeyer twins are still alive. If any further news comes in on them, I will update this post.

**********

UPDATE (August 25, 2009)

I received this fascinating comment today from film crew:

I was part of the crew that filmed the story of the anorexic twins on a number of occasions when "The Insider" was doing regular updates on their progress.

Geelong unit fire claims two lives

Sources & Links:

The Sydney Morning Herald

http://sixtyminutes.ninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=259231

http://rds.yahoo.com/_ylt=A0WTb_oeIIFJWmUBHCKjzbkF/SIG=12jdif4br/EXP=1233285534/**http%3A//abclocal.go.com/kgo/story%3Fsection=bizarre%26id=3717429

http://www.geelongadvertiser.com.au/article/2007/08/18/6191_news.html

http://www.angelfire.com/extreme4/hyperbole/mp_latestnews_article3.htm

Follow on Buzz