"CAMPBELL, Nicole Elaine,

January 3rd 1964 to April 17th 2008.

Dearly loved daughter of Pat and the late Peter Campbell, and always a proud eldest sister of Maryse ( Jim), Chantal (Drew) and Simon. Nicole delighted in her nephew Max and her nieces Kate, and new baby Sarah.

For many years Nicole managed the pain, anxiety and ravages of anorexia. She was supported at every step by her family, her family doctor Todd Walters, many members of Metropolitan United Church, and her faithful caregivers, especially Grace and Sanya.

She leaves us with comforting memories of her courage, her wicked sense of humour, her thoughtful generosity, and her determination to do things her own way right to the end. These gifts we will hold so that she will remain with us.

To celebrate her life, a concert with her favourite Metropolitan Silver Band, will be held on Sunday May 4th at 7 p.m. at Metropolitan United Church 56 Queen St. (at Church), Toronto, M5C 2Z3. Dessert and coffee will be served in the Metropolitan Centre at 7:45, after the concert.

If so desired, memorial donations may be made to Sheena’s Place 87 Spadina Rd, Toronto, M5R 2T1 at www.Sheenasplace.org , or

The Metropolitan Silver Band, c/o Metropolitan United Church as above."

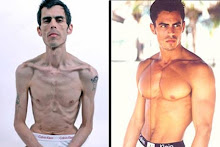

The new faces of anorexia and bulimia

Starve, binge, purge cycle on rise among women over 40

Sharon Kirkey

Canwest News Service

"Nicole Elaine Campbell was 44 years old when her heart finally stopped.

Her kidneys had given out long before; her bones were so weak she fractured both hips, her arms, collarbone, spine and pelvis.

"For many years Nicole managed the pain, anxiety and ravages of anorexia," read the obituary published after her April 17 death, and like many women with severely disordered eating, she was very good at it.

"She was so self-disciplined," her mother Patricia says.

Experts across Canada are seeing an increase in women over 40 seeking help for eating disorders -- women so rigid and obsessed about what they eat they throw out entire categories of food ("no meat, no carbs, no dairy, no sugar"). Women who hoard boxes of NutraSweet and eat nothing but dry salad for dinner. Women who starve themselves by day and rush through drive-thru windows by night, binging and purging on fast food. Women who spend all day thinking about not eating.

Some have struggled with weight and food for years. Many are relapsing after being in recovery for decades from an eating disorder they had in their teens; some never got the treatment they needed when they were younger. Others are developing eating obsessions and distorted body image issues for the first time in their lives.

Sheena's Place, a Toronto eating disorders centre, has started a support group for women at mid-life to meet demand.

"We've got women as young as 35 and women in their 60s," says program director Anne Elliott.

At Hopewell centre in Ottawa, the increase is in binge eating among women over 30.

"They're not doing so much compensating in terms of purging or over-exercising but they're binging and feeling really out of control with it, really guilty about it," says program co-ordinator Misty Pratt.

It begins slowly, like alcoholism. "Eating disorders are not just something you 'wake up' with one morning," Elliott says.

It can start with a diet and, when the feedback is positive ("You look so good!"), can lead to a slippery slide into serious restriction and the beginning of obsessive behaviour -- women weighing themselves constantly, rearranging food on a plate, refusing to eat with the family, getting up in the middle of the meal to vomit or an intense fear of weight gain and fat.

A woman can hide bulimia or anorexia to a certain point. "Because the weight loss can develop slowly over time, people get used to seeing someone really thin and don't think this person might have an eating disorder," says Elliott.

But there can be telltale signs too: thinning hair, yellowish, dry skin, sore throat and swollen glands. Elliott can sometimes tell just by the sound of a woman's voice whether she has an eating disorder. "I can tell by talking to somebody if they have been purging through their throat a lot."

For some, it's a coping strategy, a desperate grasp for control at a time of transition or crisis -- divorce, the death of a spouse, children leaving home, caring for an aging parent. Women revert to old behaviours that became imprinted in their brain.

People do all kinds of things for comfort and achieving a particular number on the scale can be seductive, says Merryl Bear, of the National Eating Disorder Information Centre.

"It allows them to feel a sense of accomplishment in a world that might feel very chaotic and out of control."

Dr. Lara Ostolosky says more older women are seeking help partly because eating disorders don't hold the same stigma they once did.

The thinking used to be there was no biological component to them, "so that if a person is having eating disordered behaviours like binging and vomiting and laxative (abuse) and starving themselves, it was all an attention-seeking behaviour. The research now says that's entirely not the case.

"There is this large biological component to this. In other words, it's a very bona fide psychiatric illness," says Ostolosky, an eating disorders psychiatrist at the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton.

"For some reason this culture is still uncomfortable with women wearing our stories on our faces and our bodies," says Kate Lum, 43, a children's author and health outreach and intake co-ordinator at Sheena's Place, who struggled with an eating disorder in her twenties.

But a woman's metabolism slows as she ages and the natural tendency is to put on weight. The more women try to defy that biological set-point, the more the body rebels.

"Throw in things like menopause and it's even more difficult metabolically. The body doesn't want to lose weight," says Ostolosky, of Edmonton.

"So the more they try to restrict, the hungrier they get, the more they binge, the more they vomit and on the cycle goes."

The behaviour becomes entrenched and and starts to exact a toll. Women begin to lose bone, their blood pressure drops and fine hair, like the downy hair of a newborn, can grow over the body as it tries to compensate for constantly being so cold.

"They're unable to work because they're binge eating and throwing up so much, or they've restricted eating to the point they can't think clearly and employers are starting to notice, or the relationship is falling apart because the husband discovers the binging and purging," Ostolosky says.

Or they seek help because of their daughters. "They're worried about their daughters, about what their own eating habits are saying. 'Why doesn't Mom eat the same food we do? Why doesn't Mom ever have dinner with us?'"

One 45-year-old woman would starve herself all day and then binge on fast food at night.

"Starting at 6 p.m. she'd go through Burger King and get her meal and eat it and then throw up. Then she'd go through McDonald's and then Wendy's and Taco Bell. Three or four in one night," says Dr. Dena Cabrera, a staff psychologist at Remuda Programs for Eating Disorders in Arizona, the largest in-patient treatment centre in the U.S. for girls and women with eating disorders.

Another woman restricted her intake to 400 to 500 calories a day: one egg white in the morning, a slice of turkey with a few carrots or celery for lunch and salad without dressing for dinner.

"If she was feeling like she needed a little pick-me-up she'd maybe throw a couple of slices of chicken on it," Cabrera says. "But usually they're vegetarians."

Nicole Campbell's mother Pat says there are as many reasons as there are stars in the sky why someone develops an eating disorder. "If we knew we would have done something about it."

Nicole was a gifted athlete and student, a musical and much-loved eldest of four children and, "looking on the surface, there was no identifiable trauma."

If Pat can trace it to anything, she thinks the problem may have started the year Nicole spent in Switzerland doing Grade 13, where she was fed a particularly rich diet and gained some weight. At the University of Western Ontario she became very picky and then, gradually, she didn't cook or eat much at all.

Throughout her 30s and early 40s, Nicole's weight hovered between 80 and 90 pounds.

"Her eating habit changed to very deprived, unhealthy things," Pat says. Nothing but soda crackers with no salt, or a certain brand of soup. "When we were together on family occasions she would eat a bit of what we had. It was this obsession. If she made a mistake and ate a proper dinner she would quickly remove herself and give it back."

Her kidneys stopped working properly, and even seemed to shrink. Five years ago, when they shut down completely, Nicole went on daily dialysis.

"The next way we noticed it, other than her incredibly low body weight, was that she became severely osteoporotic. She had numerous fractures," Pat says. "For a time she was having mini seizures and falling."

Nicole died last month of a septic lung infection. "Her body just wore out," Pat says.

The longer women live with disordered eating and the more medically compromised they become, the harder the recovery. Having anorexia is the single most important risk factor for suicide, Cabrera says. But many doctors don't look for it. The focus today is on obesity, she says, and women aren't opening up and saying, "I'm kind of restricting, or I'm binge eating or I'm having problems with food. They don't talk about it."

But when they do seek help, many women enter treatment highly motivated.

"They're tired of it. They're old enough so they have more life experience and more motivation to get better. They've seen how it's destroyed their lives and the toll its taken on their families," Ostolosky says.

"The message is, there is hope and support for people with eating disorders," says Elliott, of Sheena's Place.

"One of the first things is to break the isolation and seek medical help and find some kind of support group and counselling where you can deal with some of the underlying issues in your life, so that you can find new coping strategies that don't put your health in any kind of jeopardy."

If you, or someone you know, is struggling with an eating disorder or is preoccupied with weight and dieting, contact the National Eating Disorder Information Centre in Canada at nedic.ca, or call toll-free 1-866-633-4220. The non-profit organization has a national directory of service providers.

LINKS:

Obituary: http://umbrelladaycare.com/forum/index.php?action=recent

Follow on Buzz