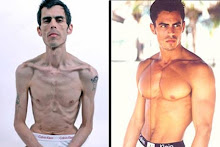

The death on November 15, 2006 of anorexic model Ana Carolina Reston has those close to her hoping the fashion industry will finally wake up to the dangers of the eating disorder.

Reston, 21, a Brazilian model who weighed only 88 pounds at the time of her death, succumbed to a generalized infection caused by anorexia nervosa, officials at Sao Paulo's Servior Publico Hospital said.

~~~~~~~~~~

"Moved by concerns over skinny models, countries have begun the controversial measure of applying legislation to the catwalks

by SIRI AGRELL

April 19, 2008

When Brylie Fowler was choosing models for a fashion spread in the second edition of her London-based magazine, Plastique, she settled on a girl whose portfolio indicated that she had a healthy, athletic frame.

But Ms. Fowler, who grew up in Oakville, Ont., said the model who arrived had a 23-inch waist and was so tiny that she resembled a baby deer as she struck the exaggerated poses of high fashion. The resulting photographs of her in a Dolce & Gabbana gown, Ms. Fowler said, were too frightening to print.

And so the magazine decided to use a common industry technique, airbrushing the image before it went to press to change the girl's appearance.

Except in this case, it made her bigger.

"It doesn't look good," Ms. Fowler said yesterday of emaciated frames. "And I'm in the business of making things look good."

The fashion industry is having a similar image crisis these days. It has been accused of promoting extreme thinness for decades, finally leading several countries to take legislative action.

This week, France introduced a law that would make it a crime to "incite" people to thinness on websites, magazines and in advertisements. In 2006, Spain announced that models must have a minimum body mass index, or height-to-weight ratio, of 18, or be banned from the runways.

And some haute couture heavyweights seem to be taking note. In the April issue of Vogue, the Prada-wearing devil herself, Anna Wintour, encouraged designers to "consider athleticism and vitality as assets in the wearing of great fashion."

But is the fashion world simply paying pouty lip service or is the industry that gave us skinny jeans and standardized size zero really ready to declare that thin is out?

"People don't even really believe it; there's not any fear," said Ms. Fowler, who began her career at the Paris magazine Citizen K. "Is this law really going to change anorexic girls out there? Are we not going to take photos of Mary-Kate Olsen?"

Skepticism of the law and its impact has been expressed by fashion insiders around the globe.

French designer Jean-Paul Gaultier was quoted as saying: "This kind of problem cannot be resolved with laws," a sentiment repeated in Canada.

In October, a group of fashion designers from Milan, Italy, attended the L'Oréal Fashion Week in Toronto and asked Fashion Design Council of Canada president Robin Kay to sign a pledge not to use skinny models in the shows. She refused.

"I said I couldn't do it," she recalled yesterday. "I can have an opinion, but I'm not going to sign that. I have not seen a need for it on our runways."

Jeanne Beker, host of Fashion Television, said she understands the impetus behind the French legislation, but not how the government plans to enforce it.

"I find it very strange that people are trying to legislate an aesthetic," she said. "We don't want to promote unhealthy images, but who's to say what's really healthy? How would it look if people over a certain weight couldn't be shown?"

Ms. Beker believes the French law, if it is ultimately passed, would be a form of censorship. But more than that, she suggests that eagerness to blame fashion for eating disorders is a cultural witch hunt akin to demonizing gangster rap or violent video games.

Fashion is a business, she said, but also a fantasy, one that is produced at great effort with the explicit purpose of being non-representative.

"These images are not to be taken literally," she said. "At every photo shoot there are 50 people scurrying around trying to get that girl to look like that. It's a fairy tale."

But the problem with the fantasy defence, critics say, is the very real nightmare of women who take those images to heart, and who carve their bodies down to unnatural sizes and unhealthy states while studying the pages of Vogue.

In 2006, Brazilian model Ana Carolina Reston died of anorexia-related illness at the age of 21 and a weight of just 88 pounds. Months earlier, 22-year-old Luisel Ramos walked off a runway in Uruguay and dropped dead from massive heart failure, also the result of starvation.

Images of the two women can be found among pictures of celebrities, such as the Olsen twins, Kate Bosworth and pre-pregnancy Nicole Richie on the so-called pro-anorexia, or "pro-ana," sites that propagate on the Internet. The French legislation also promised to crack down on these sites, where "thinspiration" photos are shared by anorexics ("anas") and bulimics ("mias") along with pictures that chronicle their own starvation.

"Imagine standing in front of the bathroom mirror and taking pictures of your abdomen every day and doing so because you want to compare all the photos to see if your efforts have led to any change," said Sharon Hodgson, a 30-year-old Web designer who lives in Halifax. "It's a recipe for insanity."

Having developed anorexia as a teen, a reaction to stress at school, she says, Ms. Hodgson entered the world of pro-ana sites in her 20s, and was soon working as a moderator on one called Miana, which has since been shut down.

Like many people who suffer from an eating disorder, she saw her weight as something over which she could exercise control, and she sought others online who "understood that coping mechanism."

The Internet was a place to trade tips and thinspiration photos, but also a vehicle to chronicle her disease, the very presence of other users acting as an incentive to push herself further toward death.

But, like the upper echelons of the fashion world to which she aspired, Ms. Hodgson said pro-ana sites are elitist, and one of her jobs was to keep out new members.

"You become strangely protective about not wanting other people to learn an eating disorder," she said.

In 2006, Ms. Hodgson went to a walk-in clinic and admitted to her disorder, only to be placed on a waiting list and never contacted again.

She now runs a website called webiteback.com that she describes as "post pro-ana," a recovery group that allows women to track their improving health instead of their downward spirals.

Creating the site helped her get healthy and she would like to see more education programs and community support for women with eating disorders.

But the French law makes her nervous, especially the move to criminalize pro-ana sites.

If she had been contacted by authorities during her days as a site moderator, Ms. Hodgson said that being treated as a criminal would have been devastating to her mental health.

"I wasn't very stable emotionally and it wouldn't have been pretty. I might have done something stupid or rash," she said. "It sounds like they're just going to throw all the mentally ill people in jail."

Stories like Ms. Hodgson's have prompted many health experts to support legislative action as a necessary next step.

Anne Elliott, the program director of Sheena's Place, a Toronto eating-disorder clinic, said there is no real divide between the world of fashion and those who consume it.

Sheena Carpenter, for whom the clinic was named, was told by a modelling agency at age 15 that her face was too wide and that she should investigate plastic surgery. She died in 1993, weighing just 50 pounds. If society isn't going to address that reality, Ms. Elliott said, perhaps the government should.

"How else is it going to change?" she asked.

Dr. Hany Bissada, of Ottawa's Regional Centre for the Treatment of Eating Disorders, also supports the French legislation.

"I think it's a step in the right direction," he said. "It's not legislating weight; it's putting a minimum level of health for people to be able to participate in this industry."

Dr. Bissada believes that women with a BMI below 18, the threshold for starvation, should not be allowed to model.

"I would love to see that enforced in Canada," he said. "I'm not asking for jail time, but a fine would be good enough."

Penny Priddy, an MP with the NDP who has long followed health issues, said she does not believe legislative action is realistic, and believes more resources should be given to educating young people about positive body image.

"I don't know whether it would withstand a constitutional challenge or whether this would be considered censorship," she said. "Are you then going to say there can be no websites that can advertise how to gamble or mix a drink?"

From her experience in the world of fashion, Ms. Fowler does not believe that BMI is an adequate indicator of health. She knows many of the fashion it-girls held out as examples of extreme thinness, and said their body shape is the natural result of genetics and their young age.

Setting a mandatory minimum BMI in Spain had only one effect, she added. Models stopped travelling to shows there.

"I don't want anyone to suffer for fashion, but I don't think the law should come into it," she said. "The onus should be on the agency to make sure the girls they provide are healthy."

At least one agent is doing so.

Next month, Ben Barry, who owns a Toronto modelling agency, will lead a team of researchers in an international study as part of his PhD research at Cambridge University in England.

Mr. Barry's agency represents models of various racial backgrounds, heights, sizes and ages, and while his advocacy has landed him on The Oprah Winfrey Show, he said the industry-wide resistance to more inclusive images is palpable.

Although Dove, a beauty-products company, has had tremendous success with its "campaign for real beauty," which employs "real" models, Mr. Barry said, many do not believe that regular-sized women can be used to promote luxury brands.

To see whether this is true, his team will survey thousands of women in England, Canada, the United States, India, China and Brazil about how models of "traditional" and "plus" sizes affect their shopping habits and brand loyalty.

He hopes his results will make the fashion world take note, but until then, he doubts anything will change.

"As long as we approach this from a health-care perspective or a government perspective, change is not going to occur," he said. "Fashion is a business, and if we're going to make change, we have to use the language of business."

Anorexia: Criteria

The following are the American Psychiatric Association's published criteria for diagnosing anorexia nervosa.

Refusal

Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height. (For example, weight loss leading to body weight less than 85 per cent of that expected; or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85 per cent of that expected.)

Fear

Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming overweight, even though patient is underweight.

Denial

Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

Missing periods

Amenorrhea in postmenarchal females. (That is, the absence of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles. A woman is considered to have amenorrhea if her periods occur only after hormone administration.)

>>American Family Physician

Anorexia: Consequences

A body suffering from anorexia nervosa is denied the nutrients it needs to function normally. To conserve energy, the body slows down, causing medical problems.

Heart

Abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure. The risk for heart failure rises.

Bone

Reduction of bone density, which results in dry, brittle bones.

Muscle

Muscle loss and weakness.

Kidneys

Severe dehydration, which can result in kidney failure.

Energy

Fainting, fatigue and weakness.

Hair and skin

Dry hair and skin; hair loss is common.

Growth of a downy layer of hair called lanugo all over the body, including the face.

>>National Eating Disorders Association, www.nationaleatingdisorders. org

Body image and eating disorders

The results of a 1995 study show that women, when asked about their shape and what is considered ideal, consistently rated themselves as much heavier. Responses in men have shown that their ideas of attractive and actual are at about the same point. BMI stands for body mass index.

7 million women in the U.S. suffer from eating disorders, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Eating Disorders.

10% report onset of illness at 10 years or younger.

2% of Canadians are considered to be underweight.

18...

BMI below which doctors consider a person to have an eating disorder.

27...

Average Canadian BMI score.

38.9% of Canadians are considered to be a normal weight (18.5 to 24.9 BMI score)

59.1% of Canadians are considered to be overweight or obese.

SOURCE: STATISTICS CANADA, ANAD.ORG, FEMALE FEAR OF FAT , FALLON AND ROZON STUDY (1985)

Click on the following links to read more about anorexia, bulimia, lanugo, Ana Carolina Reston, Luisel Ramos, France's new anorexia law, Sharon Hodgson & We Bite Back:

WARNING TO ANOREXICS: LANUGO IS NOT PRETTY

ISABELLE CARO and ANOREXIA: HER TRAGIC CHILDHOOD & HER CURRENT STRUGGLE TO SURVIVE...

THE DEADLY KIMKINS DIET & EATING DISORDERS...

KIMMER...MEET ISABELLE CARO...

FRANCE TABLES NEW "ANOREXIA" LAW

LINK:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/LAC.20080419.THIN19/TPStory//?pageRequested=all

Follow on Buzz

2 comments:

Great post, Medusa!

I've linked to it in my blog.

My blog: Weighing The Facts

Interesting and very very sad :(

Post a Comment